Office

First Canadian Place

100 King Street West

Suite 5600

Toronto, Ontario

M5X 1C9

Canada

By Michelle de Cordova, Principal and Blythe Clark, Director, ESG Global Advisors

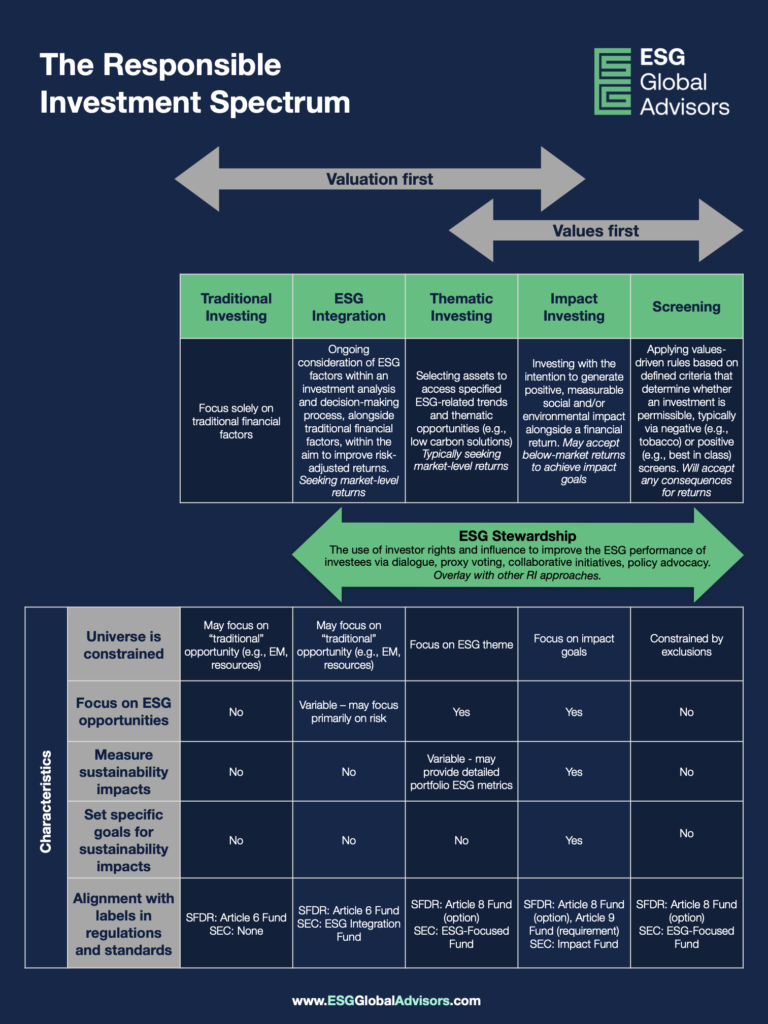

In March 2023, we published Reimagining the Responsible Investment Spectrum: Why Definitions Matter in Dispelling Myths About ESG. That piece questioned whether the typical practice of representing responsible investment approaches on a continuum from “valuation first” to “values first” accurately reflected the current scope and focus of responsible investment and discussed the importance of clear terminology to combat greenwashing criticism at a time of growing interest and polarized debate about ESG.

In November 2023, the CFA Institute, the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (GSIA) and the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) published Definitions for Responsible Investment Approaches, a harmonized set of definitions for common responsible investment terms.

(jump to a section by clicking the links below)

As advisors who are frequently called upon to explain responsible investment to investors and investee companies, we welcome this combined effort to clarify terminology that has often been a source of confusion. In discussing the definitions and accompanying guidance, we found much to appreciate – but were also left with some questions.

We had two overarching observations:

Our observations about each of the definitions and accompanying guidance are set out in more detail below.

| CFA/GSIA/PRI Definition (November 2023) | Observations |

|---|---|

| ESG Integration “Ongoing consideration of ESG factors within an investment analysis and decision-making process with the aim to improve risk-adjusted returns.” | The accompanying guidance encourages investors to avoid using the term “ESG integration” without explaining in plain language how ESG factors are considered in the investment process. This is helpful, because many funds claim to undertake ESG integration without providing substantive information about how it is done. Furthermore, better disclosure on integration methodology could advance ESG practice by revealing which approaches best correlate with enhanced returns. |

| Thematic Investing “Selecting assets to access specified trends.” | The definition aligns with our contention that thematic approaches should not be assumed to prioritize values over valuation. By positioning thematic investing as investment to access opportunities associated with systemic changes such as the transition to a low-carbon economy, the definition distinguishes between investment in ESG trends, and investment in ESG topics that are simply trendy. |

| Impact Investing “Investing with the intention to generate positive, measurable social and/or environmental impact alongside a financial return.” | The accompanying guidance emphasizes that impact investing requires a “theory of change” – “a credible explanation of the investor’s contributory and/or catalytic role, as distinct from the investee’s impact.” It is not enough simply to invest in companies with net positive impact. This requirement for a proactive investor role could prove challenging. For example, it appears to go beyond the definition of “sustainable investment” under Article 9 of the European Union’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) fund classification, although Article 9 funds are often considered to be impact funds. SFDR’s definition of “sustainable investment” focuses on the environmental or social impact created by the investee, not the contributory role of the investor. A higher bar for investors to be able to “claim” the measurable ESG impacts of their investments could also have unintended consequences for companies that are creating positive change, and currently benefit from the inflow of capital seeking impact opportunities. If some would-be impact investors abandon this approach to responsible investment altogether because they are unable to articulate a credible theory of change, change-maker companies could experience negative impacts in terms of access to and/or cost of capital. |

| Screening “Applying rules based on defined criteria that determine whether an investment is permissible.” | The definition highlights that the basic concept of applying rules to determine whether an investment is permitted is essentially the same in values-based screening and in traditional approaches that restrict the investment universe based on considerations such as market capitalization or geography. While the definition sets out a range of good practices for disclosure on screening methodology, it does not squarely address what happens when there is a conflict between values-based screening criteria and portfolio value. Blurring the lines between traditional portfolio constraints and values-based screening could be confusing, especially for fiduciaries. In practice, investors applying the types of screening described in the definition – negative, positive, best-in-class, and norms-based – must be prepared to accept any associated consequences for returns, whether positive or negative. |

| Stewardship “The use of investor rights and influence to protect and enhance overall long-term value for clients and beneficiaries, including the common economic, social and environmental assets on which their interests depend.” | PRI stated previously that not all investor-investee interactions are engagement: there should be a focus on seeking change in ESG practice or disclosure. The definition and accompanying guidance go even further, stating that “using influence to promote short-term performance or the performance of individual companies, industries or markets, without regard to overall value, does not constitute stewardship” and that “the term should not be used to refer to such activities as proxy voting and engagement unless these actions are undertaken to protect and enhance overall value.” While excluding routine interactions helps to counter greenwashing, the definition could also exclude short-term engagement with individual companies on ESG risks with significant implications for their value. Leading practitioners certainly distinguish between portfolio-wide strategic engagement on systemic ESG issues such as climate change, and tactical engagement on ESG-related risks and controversies at specific companies – but typically consider both to be part of their overall stewardship approach. “Downgrading” tactical ESG engagement with individual companies could also have unintended consequences for real-world sustainability. It is unclear how the definition aligns with the expectation under the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) guidance on responsible business conduct for institutional investors that investors should exercise leverage to address significant adverse impacts of investees for the environment, human and labour rights, and anti-corruption. While in some cases these impacts may also affect long-term value for clients and beneficiaries, the OECD guidance – as well as SFDR’s Principal Adverse Impacts (PAI) provisions, which draw upon it – focuses on protecting the environment and affected stakeholders, not on protecting portfolio value. If stewardship is defined solely in terms of value, another word might be needed to describe interactions driven by responsibility to third parties under international norms. |

In our earlier piece, we reimagined the “Responsible Investment Spectrum” considering the following aspects:

Our review of the harmonized definitions has led us to revise some of the terminology and definitions in our Responsible Investment Spectrum, while retaining others.

At a time of growing interest and debate about ESG, clarifying the definitions of responsible investment approaches has never been more important. Doing so might open new ESG opportunities for fiduciaries and even help to bridge at least some of the gap between ESG proponents and sceptics. We welcome the new harmonized definitions as an important contribution to this goal.

Whether an investor focuses on valuation, values, or a combination of the two, we believe the following steps are critical to establishing an effective responsible program that can stand up to any kind of scrutiny:

For companies, understanding how the capital markets in general, and key current or potential investors specifically, are grappling with responsible investment is key to designing a corporate ESG strategy that maximizes access to capital and enhances long-term value. This information is a critical input to ESG materiality assessment, ESG strategy development, and devising an effective approach to communication and disclosure on ESG.

Need help with responsible investment strategy, or with enhancing or communicating the corporate ESG approach? ESG Global offers customized services for investors (asset owners and asset managers) with portfolios of different sizes and across asset classes. We also offer a comprehensive range of ESG strategy and reporting services for companies. Visit Our Services to learn more.